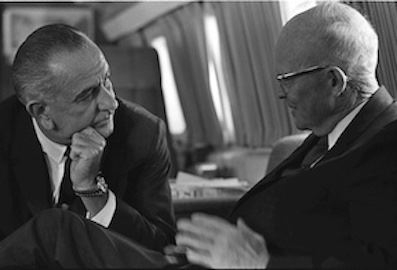

On January 20, 1961, Eisenhower’s presidency ended, and John F. Kennedy’s began. As a two-term President, Eisenhower had kept the nation out of war. He had been a faithful and trustworthy leader. After half a century of hard work, it was time for his retirement. He more than deserved it.

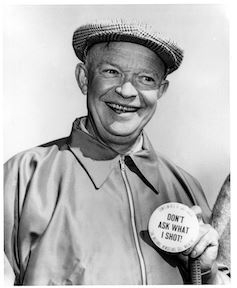

Upon entering the office of the Presidency, Dwight Eisenhower had resigned his permanent commission as General of the Army. President Kennedy reactivated his commission as a five star general in the United States Army. With the exception of George Washington, Eisenhower is the only United States President with military service to reenter the Armed Forces after leaving the office of President.

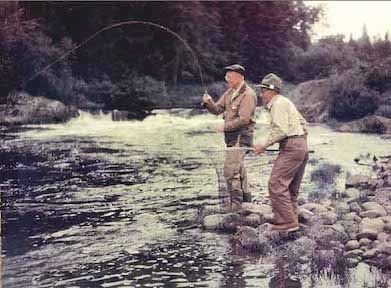

After leaving the White House, Ike and Mamie went to live at their 190-acre farm in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. They had bought it in 1950, and it was the only home they ever owned. It is located next to the famous battlefield of the Civil War and not far from the land on which Eisenhower’s grandfather, Jacob, had lived before heading west.

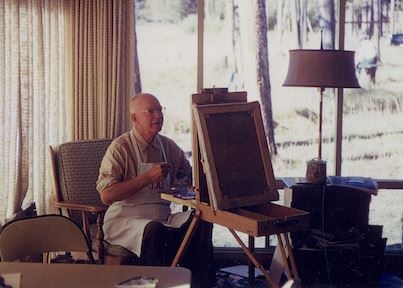

While a modest farmhouse on the outside, their retirement home was filled with elegant furnishings, the pick of the hundreds of gifts Eisenhower had received over the years from heads of state and American millionaires. Ike and Mamie had had to be separated so much during their marriage, but they made up for it now by spending long hours together on their sun porch, overlooking the fields, reading, watching television, or painting.