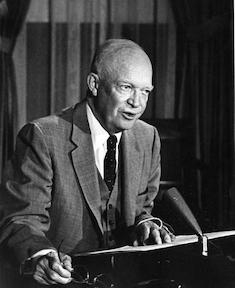

Dwight D. Eisenhower signs the

Civil Rights Act of 1957 in his

office at the naval base in

Newport, Rhode Island.

“There must be respect for the Constitution — which means the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Constitution — or we shall have chaos. We cannot possibly imagine a successful form of government in which every individual citizen would have the right to interpret the Constitution according to his own convictions, beliefs and prejudices. Chaos would develop. This I believe with all my heart — and shall always act accordingly.”

-DDE, Letter to his friend Swede Hazlett, boyhood friend, July 22, 1957

If Dwight D. Eisenhower had known in 1956 how contentious and difficult his second term would be, he might have been even more reluctant to consider reelection. From Election Day 1956 until he left office on January 20, 1961, it seemed that his job was one crisis after another.

Dwight D. Eisenhower has a special

broadcast on the Little Rock situation

Eisenhower lost two valued members of his team during his second administration: Sherman Adams and John Foster Dulles. Adams was both liked and respected by the White House staff for his extraordinary management and organizational skills. Considered a “scrupulously” honest man, Adams, nevertheless, made the mistake of accepting gifts from a friend, a wealthy New England industrialist.

Adams, “informally, the president’s White House chief of staff,” had acquired an impressive list of enemies in Congress and among some of Eisenhower’s close friends. When they learned of his indiscretion, it was only a matter of time before Democrats in Congress began demanding his resignation. By early September 1958, the clamor had reached a pitch that Eisenhower could not ignore. Five days after meeting with the president, Adams submitted his resignation. Wilton B. Persons, Adams’ second in command, replaced him. Adams’ New England reserve and bluntness were replaced by the warmth of Persona’s southern charm and sense of humor.

In late 1958, John Foster Dulles was 70 years old. He had been treated for cancer before and now underwent additional medical tests to uncover the source of new pain. Although the cancer had come back, Dulles put off treatment to continue his work until early February 9, 1959. Finally, in late February 1959, Dulles took a leave of absence to enter the hospital.

Throughout the spring, Dulles remained in the hospital; Eisenhower called him daily to report on the progress of the test ban agreement. Eisenhower was incensed that a number of Democratic senators, knowing that Dulles was literally on his deathbed, chose this time to criticize his policies and demand his resignation.

June 23, 1958 - Dwight D. Eisenhower receives a group of prominent civil rights leaders.

Left to Right: Lester Granger, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., E. Frederic Morrow, Dwight D. Eisenhower,

A. Philip Randolph, William Rogers, Rocco Siciliano, and Roy Wilkins.

After a slow and painful decline, on May 24, 1959, John Foster Dulles died. Dulles had been the president’s closest advisor, an able and devoted colleague. His knowledge of every aspect of public affairs and his lifetime of experience were irreplaceable. Eisenhower felt his loss acutely. Under Secretary of State Christian Herter became the new Secretary of State on April 20, 1959.

For President Eisenhower, 1957 was a nearly impossible year. First, the struggle and the political expediency necessary to secure civil rights legislation had disgusted him. Before it was even signed, the school desegregation disaster at Little Rock was upon him. Immediately after, Sputnik threw the nation into a crisis of self-confidence and worry with demands for education reform, fallout shelters, space exploration, and even more unnecessary — in his opinion — weapons. The president had done his best to reassure the American people that the United States was secure and to keep the lid on a defense establishment that threatened to spend the country into oblivion. Then in November, just before Thanksgiving, he had suffered a minor stroke. To make things even worse, 1957 was a recession year.

Despite doing all he could to keep the nation at peace, secure and prosperous, the criticism gathered momentum every day by the end of 1957. Newspaper columnists, particularly had begun to question how well he had done his job. The president was criticized for the Civil Rights Act and for the recession. What cut most deeply, however, were charges that he had “lost” the space race to the arms race. Moreover, Dwight D. Eisenhower still had three more years to endure.

The president had been working at his desk on November 25, 1957, when he suddenly lost the ability to hold objects or to speak. President Eisenhower, age 67, had suffered a stroke. For several days, he was unable to communicate intelligibly, but he quickly recovered. Through not obvious to others, after the stroke, he sometimes switched syllables in words. That winter was frustrating, and the subtle effects of the stroke on his health made his job even more demanding.

Dwight D. Eisenhower and Nikita

Khrushchev meet at Camp David.

A year later, as 1958 turned to 1959, Eisenhower had just two years left in his term. He planned to use them to establish a legacy of peace. As he looked forward to taking on his new objective, his characteristic optimism returned. He planned to do all that he could to accomplish a nuclear test ban with the Soviet and move toward a disarmament that might offer a future peace.

President Eisenhower would complete three arduous goodwill tours in the last two years of his presidency. The first lady had been concerned about the effects of the trips on his health. She would not accompany him, however, as she had health concerns of her own. But Eisenhower was resilient. During one of the trips, a reporter traveling with the president wrote to tell her that, at 68 years old, he was holding up far better than the press!

The first trip in 1959, to the Middle East, India, and Europe, was an overwhelming success as would be the rest. The crowds cheered President Eisenhower in welcome. Queen Elizabeth II even sent him a handwritten note of congratulations. In late February 1960, he made a second tour, this time to Latin America, that lasted two weeks and made thirteen stops. Eisenhower met with four presidents and made a total of 37 speeches. The last goodwill tour, June 1960, lasted two weeks. The president made eight stops in the Pacific and East Asia, and visited Alaska and Hawaii, which had only the year before become new states in the Union.

American flag which was carried in the Corona capsule

retrieved from Discoverer XIII.

ust one month before the May 1960 Paris summit with Khrushchev, Eisenhower’s high hopes for détente with the Soviet Union and possible progress towards disarmament and peace were dashed. The U-2 incident had taken place just before the much-anticipated summit. Although it was clear that Khrushchev had made up his mind to scuttle the peace talks even before that, the U-2 fiasco had further complicated the picture and set back U.S.-Soviet relations.

As the 1960 presidential year neared, questions arose as to Eisenhower’s successor. Richard Nixon had been a member of the Eisenhower administration for eight years. The vice-president had performed well and had been a loyal team member. Yet Eisenhower and Nixon were not particularly close nor was it a comfortable relationship for either man.

Back in 1952, Nixon had expected more support from Eisenhower during the Checkers crisis. When it came only after his triumphant speech, he had felt some resentment. Over the years, the vice-president had played an active role in the administration and he was willing to do more. Nixon attended high level meetings such as those of the National Security Council and had contributed to the discussions. He had even traveled as a special representative for the president on a number of occasions. When Eisenhower had his heart attack in 1955, everyone judged that Nixon had responded admirable and responsibly. Nonetheless, Eisenhower had lingering concerns about whether his vice-president was ready to take on the responsibilities of the presidency.

Dwight D. Eisenhower tours the

George C. Marshall Space Flight

Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

Even if Eisenhower harbored irreconcilable doubts about Richard Nixon, he determined that the Democratic ticket was far worse. Moreover, the goals for the two men in early 1960 — or even as early as 1959 — were at odds. Eisenhower was focused on building his legacy and, understandably, Nixon was preparing for his own presidential run.

Because his doctor advised against it for health reasons, Eisenhower campaigned for Nixon only on a limited basis for most of the presidential campaign in 1960. Too, it was important for the vice-president to distance himself from the criticism directed at the Eisenhower administration and to establish himself as a presidential candidate in his own right. When Eisenhower did campaign, he tended to focus on the accomplishments of his own presidency rather than Nixon’s qualifications to be president. The worst gaffe occurred when Eisenhower was pushed one time too many by reporters for a specific example of something that the vice-president had contributed to the Eisenhower administration. Eisenhower, extremely irritated at the never-ending interrogation, answered, “If you give me a week, I might think of something. I don’t remember. “ He had not intended to insult the vice-president, but the damage to his campaign was the same.

Eisenhower advised Nixon that he should not participate in the 1960 presidential debates. The president felt that Nixon had little to gain and it would give Kennedy too much attention. Nixon decided to go ahead anyway. Before the first debate, Eisenhower counseled Nixon to present himself as more a statesman than a partisan. As a result, Nixon came across as too mild when compared with Kennedy’s more aggressive style. With the campaign coming to a close and the picture not looking good for the vice-president, Eisenhower campaigned more vigorously.

When John F. Kennedy was elected in 1960, Eisenhower viewed it as a rejection of his own presidency. He was very depressed by the outcome. For the past eight years, he had worked ceaselessly on behalf of the American people, and, to his way of thinking, this was a rejection of all he had accomplished at a great cost to his health and reputation.

his successor, John F. Kennedy, leave the White

House to ride together to the Capitol for the

inauguration of Kennedy as 35th President of the United States.

On December 6, 1960, Eisenhower met with President-elect Kennedy at the White House to brief him on policies and problems that he would have to deal with soon. Though Eisenhower had had little regard for candidate Kennedy, he changed his opinion, at least temporarily, after this meeting. Kennedy had impressed him with his earnestness and his questions. The meeting between the two men ended on friendly terms. They would meet once more, on January 19, the day before the Inauguration.

That night, Washington, D.C., experienced such a snowstorm that much of the White House Staff, unable to get home, had to bunk in the bomb shelter of the White House basement. The next morning, Eisenhower, for the first time in eight — or even nineteen — years, had little work waiting for him. He spent much of the morning reminiscing with his secretary Ann Whitman. When it came time for the Eisenhowers to say farewell to the White House domestic staff, there were many tears as each member of the staff received a personal goodbye.

The Eisenhowers hosted a coffee for the Kennedys and the Johnsons and other Democratic leaders, at the White House before Eisenhower and Kennedy took the traditional drive down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol. At noon, Chief Justice Earl Warren swore in the new president, the youngest ever elected to office. After the ceremonies, the Eisenhowers slipped away to join friends and, now former, cabinet members for a luncheon. Afterwards they would drive home to Gettysburg. Dwight D. Eisenhower, for the first time in decades, was now a private citizen. He looked forward to the freedom and leisure of a long-awaited and much-deserved retirement.

This content is from The Eisenhower Life Series: Called to a Higher Duty, an educational series written by Kim Barbieri for the Eisenhower Foundation, copyright 2002. Funding was provided by the Dane G. Hansen Foundation and the State of Kansas.

For a complete timeline of Dwight D. Eisenhower's life, visit the Eisenhower Interactive Timeline.

Eisenhower Foundation

Eisenhower Foundation