Over six million women took to the workforce when the men went off to fight during World War II. Some of the positions that needed filling were typists, farm workers, taxi and bus drivers, and factory and shipyard workers. A large number of the jobs were on assembly lines in factories that produced munitions and war supplies. Propaganda was distributed to recruit women to “Do the job he left behind.” Thus, Rosie the Riveter was born.

One such Rosie was Connie Palacioz (left). Now 93, she shared her story in a March program at the Eisenhower Presidential Library. Following high school graduation, Palacioz took a job with Boeing in Wichita, Kansas. She spent about two weeks in training as a riveter, earning $0.50/hour, before she was ready for the B-29 assembly line, where she would make $0.75/hour. All Palacioz needed was a bucker; the person working inside the plane. The bucker held in place a metal bar that acted as an anvil as the rivets were inserted. The back of the rivet mushroomed out against the bar, keeping the rivet secure. She found her bucker in Jerri Warden, with whom no one would work because she was black. Palacioz, being Hispanic, had no qualms about working with Warden, who turned out to be a very good bucker, and the team produced four B-29 nose sections per day.

Palacioz could not have known that she would be reunited nearly 60 years later with a bomber she helped build in 1944. A B-29, nicknamed “Doc,” returned to Wichita for restoration after sitting 42 years in the California desert.

“When I saw the plane in 2000, it was in pieces!” Palacioz exclaimed. However, the nose section, which she and Warden built, was complete except for broken glass. In fact, only seven of their rivets were missing.

Palacioz joined Doc's restoration effort, volunteering three days each week for 16 years. “I cried when I saw it fly,” she said, “thinking of some of the people who worked on the restoration but passed away before the flight.”

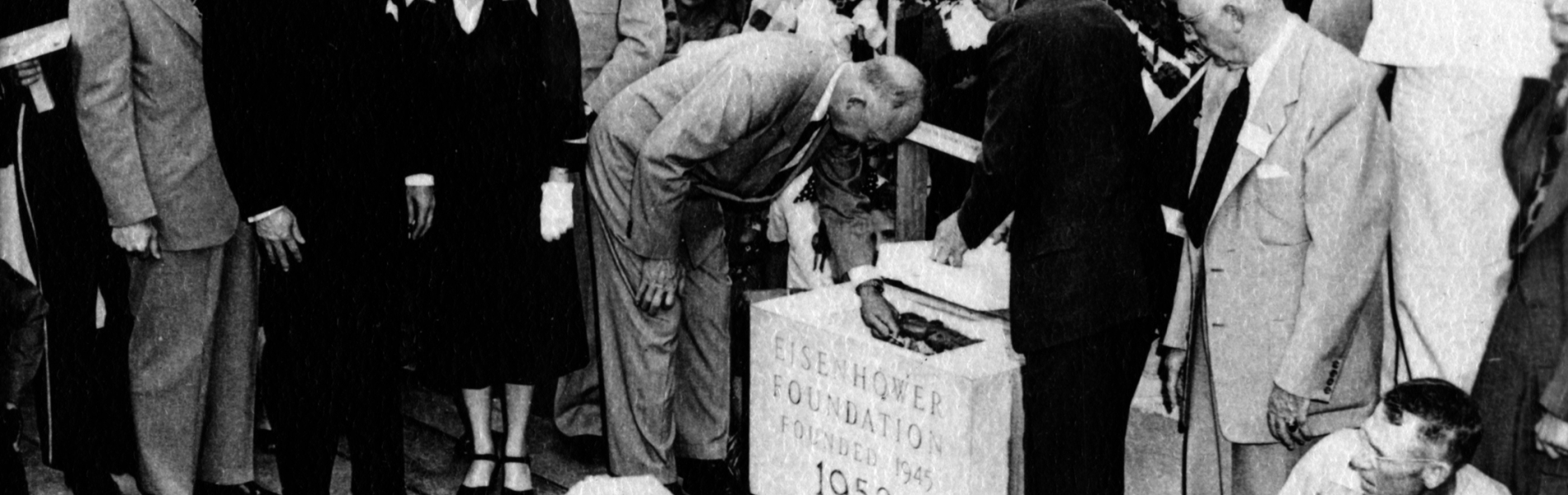

Eisenhower Foundation

Eisenhower Foundation